In a world where 2D and 3D animation dominate, Nigerian filmmaker Esther Kemi Gbadamosi has carved her own unique path through the intricate art of stop-motion animation.

From her early beginnings as an engineer and documentarian to discovering animation through playful experiments with her child’s toys, Esther’s journey is a testament to creativity born from curiosity and perseverance.

Today, she stands as one of Nigeria’s foremost voices in stop-motion, blending craftsmanship, storytelling, and cultural pride to create works that have gained international recognition.

In this exclusive interview, she shares insights into her creative process, the challenges of thriving in a male-dominated industry, and her inspiring vision for the future of African animation.

Q: Let’s start with your story how did you first fall in love with stop-motion animation, and what drew you to this rare art form in a country dominated by 2D and 3D animation?

I started my animation journey in 3D animation as I was convinced it would be my future career. Animation hadn’t picked up then. Most of my earnings at that time came from making documentaries for government, corporate organisations and individuals.

I had no idea there was any form of animation called stop motion. I worked on a 3d animated series ‘Passionate Hands’ in 2010 just before I got married, but I had to pause at the animation stage due to overwhelming symptoms from pregnancy in 2012.

It was then I started buying children’s toys, pose them and take pictures. I loved it! The responsibilities of being a young parent made it difficult to quickly go back to 3d, but I enjoyed working with the dolls.

It took a couple of years to discover it looked like an animation form called stop motion animation. I started learning more from Youtube, coming up with new ideas and created lots of sequences.

By 2019, we made our first short stop motion animated film and it went to a couple of international festivals. Then I realized there was a possibility in actually working as a stop motion filmmaker but I was scared to focus on something unknown.

The COVID lock down made the decision easier along with some candid learnings I got from Rendacon.

The French collaboration with Animation Nigeria has also played a major role in helping us get better alongside support from US Missions, Berlinale, Access Bank, and Flourish Africa, amongst others.

Q: Stop-motion is often described as “animation with patience.” As a team leader, how do you keep your crew motivated through such a painstaking and time-intensive process?

Good stop motion requires a lot of patience. In actual fact, the more patience the better. There have been times we would spend days on a sequence and then have to start again to make it better.

It doesn’t have the undo button like 3d animation. A couple of my initial team members on stop motion projects got tired and left. Many Nigerians don’t have the stop motion kind of patience, it shows in our attitude to traffic gridlock.

It has taken some level of result and recognition for team members to truly appreciate the fact that it’s worth the time and effort. The patience in stop motion can be quite rewarding.

Q: Being a woman leading in a male-dominated industry already comes with unique pressures. How has your gender shaped your journey both the challenges and the strengths in Nigeria’s animation space?

Naturally, everyone experiences challenges. Most of the time, I don’t think about my ggender. But as woman in animation, societal expectations, biological restrictions and family responsibilities can cripple strides in your career.

You really have to be intentional. Sometimes you work with men who find it difficult to work with a female leader, we always need to find non-confrontational ways to get things done.

And as we make progress, the society also tries to ensure a certain level of female representation. This helps create new opportunities.

Q: Stop-motion requires both artistry and craftsmanship building sets, puppets, lighting, and movement by hand. How do you balance creativity with the technical demands of the craft?

I’ve always loved to design and make things. My mum was a teacher in my early years, so I helped her with instructional materials and craft work.

My first business was a craft business, I also made birthdays cards before mobile phones were used for birthday messages.

In university, I studied Engineering, then learnt animation and filmmaking on the side. Spent most of my working years as a cinematographer.

All these skills combine beautifully in stop motion. I feel I was prepared for it, long before I knew it even existed. So balancing artistry and craftsmanship is exciting as it come naturally for me.

Q: Many Nigerian studios focus on digital animation because it seems faster and cheaper. What do you think stop-motion offers that digital mediums can’t?

It has a very strong international appeal. Globally, the stop motion community is small with a lot of visibility considering it’s size.

If we get it right, we can reach audiences Nollywood live action films may never be able to reach. Stop motion may be quite slow but can be much cheaper, if you choose a cheaper medium and put in a lot of personal effort and time. That was how I made most of our early films.

Q: Can you walk us through a typical production day on a stop-motion project? What does your workspace look like, and what kind of skills go into bringing a scene to life, frame by frame?

A typical production day on our stop motion project is similar to that of a live action film. The difference is that actors/performers are moved manually and pictures are taken to capture that movement.

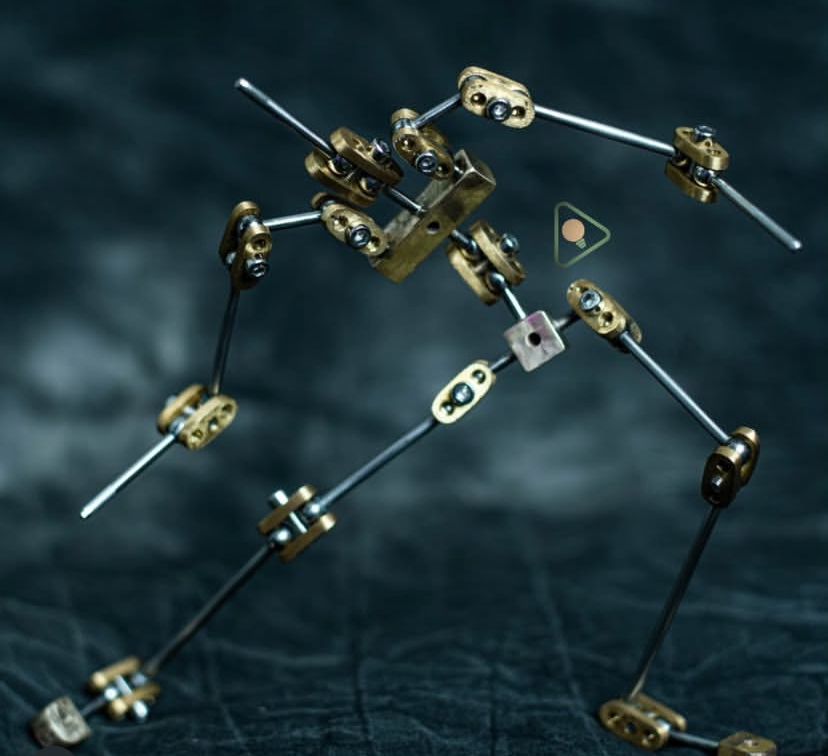

Our workspace is arranged to handle the key elements of our films, from building sets, to fabricating armatures, to making puppets, painting, costumes, 3d printing and filming.

It feels like a mechanical workshop sometimes, at other times, like an art museum. We write, draw, construct, machine, braze, sculpt, paint, sew, 3d print, animate and shoot to bring each scene to life.

Q: Funding and resources are major issues for Nigerian animators. How do you overcome the unique logistical and financial challenges of producing stop-motion, which is often more time-consuming and material-heavy?

The moment we decided we were going to focus on stop motion animation, we recognised that funding may be limited.

We came up with a grant based business model to help with funds. This particularly helped with infrastructure and logistics.

In the long run, we recognise this may be limited, so we are finding ways to work with film based products and merchandise, amongst other things.

Q: As one of the few leading women in this field, what message would you give to young Nigerian girls or students who think stop-motion is too complex or “not for them”?

Stop motion isn’t complex, in fact it’s more accessible than other forms of animation. It requires much less capital, just more time.

You do not need a large team or set. You can work alone and get something done right from the beginning. You can comfortably use your phone.

To work in stop motion animation, you must really want to. Don’t rule it out because of complexity if you already have the required talent and interest.

Q: In your opinion, what will it take for stop-motion animation to gain more visibility and support in Nigeria from both the audience and investors?

Recognition, strategic engagement, innovation and capacity building. With more external recognition, there would be more visibility and engagement.

We would need to build on this for more audience awareness, familiarity and interest. As our quality improves in puppetry and animation, audiences wouldn’t even notice the medium, they’ll just be entertained.

That’s why we decided to take time to build a high quality ball and socket armature system, made from stainless steel and brass.

Got some of these skills working on a stop motion feature film in France. It’s the first time its been made in Africa.

This is definitely a game changer for stop motion in Nigeria. Quality and engagement will naturally attract investors.

Q: Finally, what’s your vision for the future both for yourself and for the stop-motion animation industry in Africa? How do you see it evolving over the next 5–10 years?

I look forward to more capacity building programmes for stop motion. This will naturally lead to more high quality animated films telling African stories globally.

Our younger kids will have dedicated channels of Africa stories. Stop motion is indeed great for children! Our unique stories will travel in leaps and bounds.

Our new Radioxity Stop Motion Armature Kit will hopefully play a crucial role to triggering these landmark moves in this space giving wings to local stop motion talents as they share their skills on different projects around the world.